Proc. of

Avocado Topworking Update 1990

Gray

Martin and Bob Bergh

Department

of Botany and Plant Sciences,

Abstract. As total avocado acreage shrinks in

LARGE TREES (more than 25 cm in diameter)

Past

Historically,

large trees were "notch" ("sawkerf")

grafted in early spring. A skilled propagator can achieve excellent results

with this graft; tree growth is vigorous, percent take is high, and the

scion/stock union is strong and well-healed. However, this propagation

technique is quite difficult and requires specialized tools. The procedure is

slow, and also is best performed with large-diameter scion wood.

Present

Bark grafting. Bark grafting

using large-diameter trees has not generally been very successful. It helps to

reduce the thickness of the bark using the edge of a pruning saw blade, or

other shaving tool, to make the bark less brittle for scion insertion. Also,

the standard one-inch wrapping tape generally does not provide adequate

pressure on bark and scion to create a strong cambium attachment. Roofing

staples have been successful in binding the scion tightly, but as the scion

grows and enlarges, the staples pinch, restricting expansion, and creating a

permanent weakness at the graft union. Small nails or brads have been used with

limited success. This procedure requires more time and labor.

Summer shoot grafting. To

commercially graft large acreage quickly and economically, Mr. Richard Marocco, of Fallbrook Ag-Laboratories, Inc.,

The

summer shoot grafting technique requires stumping trees at about 60 cm early in

spring after the danger of frost has passed. From the mass of shoot regrowth, both from the stump and the rootstock (below

ground), 3 to 4 vigorous shoots are selected, of which two or more are grafted

with a modified splice graft in mid- to late-summer. Success rate with this

graft is high, but it is not without some disadvantages. First, grafting late

in the year requires the use of freshly picked summer wood. Unlike dormant wood

used for spring grafting, summer wood cannot be cold-stored for prolonged

periods of time. Second, there may be erratic stump regrowth

from any of several causes: inherent tree variability, excess soil moisture

accumulation during a period of no evapotranspiration

requirement, and soil moisture deficit after regrowth

activity. Third, very late-season grafting frequently does not produce sizable

trees before the cold of winter. Thus, danger of cold damage is more likely on

summer-grafted trees. Grafts must be firmly staked; the stock shoot attachment

and the fragile scion/stock attachment is vulnerable

to breakage early in the graft development.

Future

Grafting over-wintered suckers. A

promising new approach is to stump the trees as for summer shoot grafting, but

to delay the grafting until the following spring. By allowing the tree to regrow for about one year, the original stumping shock is

past, and initial graft growth response is vigorous. (Conversely, summer shoot

grafting failure can weaken the tree so that it is permanently injured by

summer heat stress or later winter cold.)

Similar

to summer shoot grafting, two or more over-wintered shoots should be

bark-grafted in early spring. The shoot will have green bark, and will

generally slip year-round. Early season grafting will establish a long growing

season for the young graft, although grafting too early may result in freeze

damage. By keeping one or two nurse limbs until graft growth is healthy and

about a height of 30 cm, the vigor of the tree and growth cycle of the stump is

sustained. Additionally, although stakes are still required to prevent

top-heavy shoots from breaking, staking is not as critical as for other graft

methods; the active cambium development of the young shoot combined with a full

season of growth usually produces a smooth and complete stock-graft union that

is quite strong.

Currently,

there are no production data comparing summer shoot

grafting with over-wintered shoot grafting. In one trial using the 'Gwen'

cultivar, some fruit was observed on the summer shoot grafted trees less than

one year from grafting. The economic value of this crop is relatively small,

and may retard early tree development; vegetative growth is suppressed by the

burden of maturing fruit and so these fruit should probably be removed.

SMALLER FIELD TREES (« 20 cm in diameter)

Here

the bark graft works well on the original stump cut. Grafting is generally done

after the danger of frost and requires slipping bark. Commercial propagator Mr.

Alvin Lypps of

Budding

Budding

is generally not recommended for avocado, particularly in topworking.

The protruding nature of the avocado bud is susceptible to physical damage from

the plastic tape wrap required to protect the small bud-shield from seasonal

dry heat. Yet, if performed successfully, budding can be a relatively easy

propagation method, and can utilize buds from immature or green succulent

shoots, not typically suitable for grafting. It requires young bark, such as on

sucker shoots.

A

successful procedure is to use a standard ‘T' bud cut, wrapping the bark over

the bud-shield with plastic tape, leaving the bud eye exposed. Then, second-wrap with a light-mil (1 mil) tape that is elastic enough

to prevent bud damage. The second wrap is removed after a period of

about 2 weeks to prevent sealed moisture from causing rot and after enough time

for the bud-shield attachment to be complete. At such time, the budded shoot is

cut 15 to 20 cm above the bud to force bud growth and to remove growth

competition from the terminal dominant shoots. A cut through the bark just

above the bud may additionally be helpful in forcing the bud to grow.

GRAFT CARE

Wrapping

Perhaps

one of the most important contributions to the success of grafting since

plastic tape and asphalt emulsion is a wax-like stretchable tape called 'Parafilm’R. The material is now used by

propagators on different species, but its usage on avocado owes its popularity

to Rick Marocco of Fallbrook. Although there are many

different techniques using the Parafilm product, the

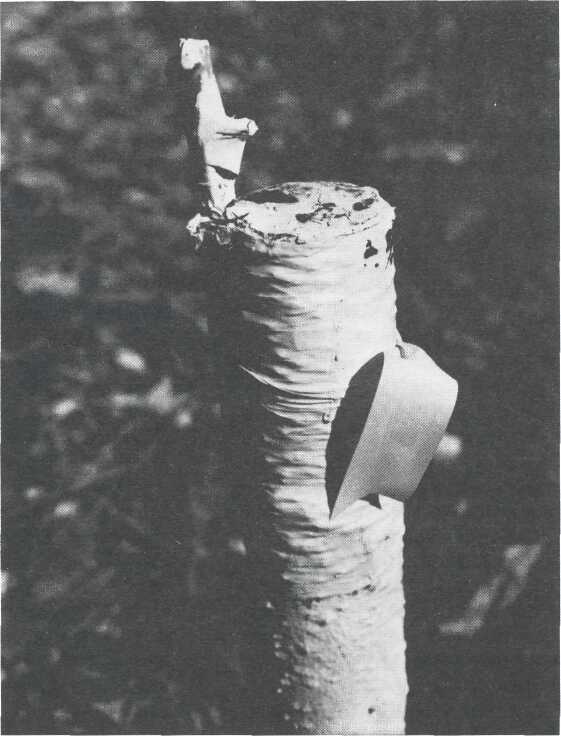

common use is to wrap the entire scion, stem and buds (Fig. 1). Buds grow

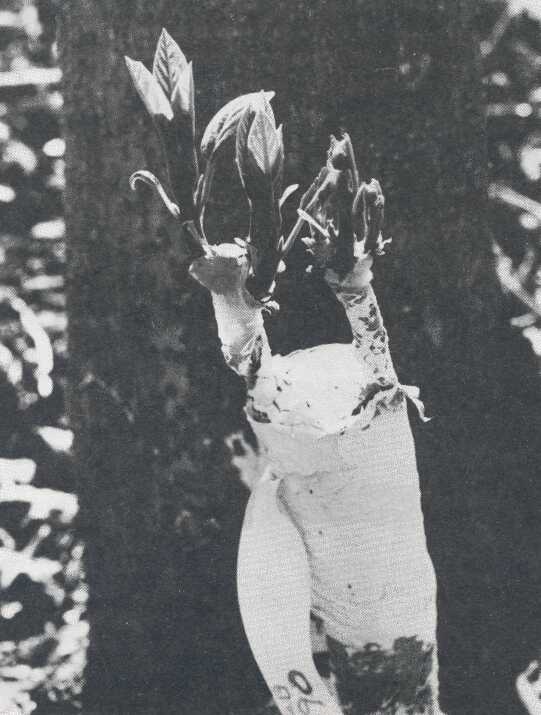

through the Parafilm and therefore removal is not

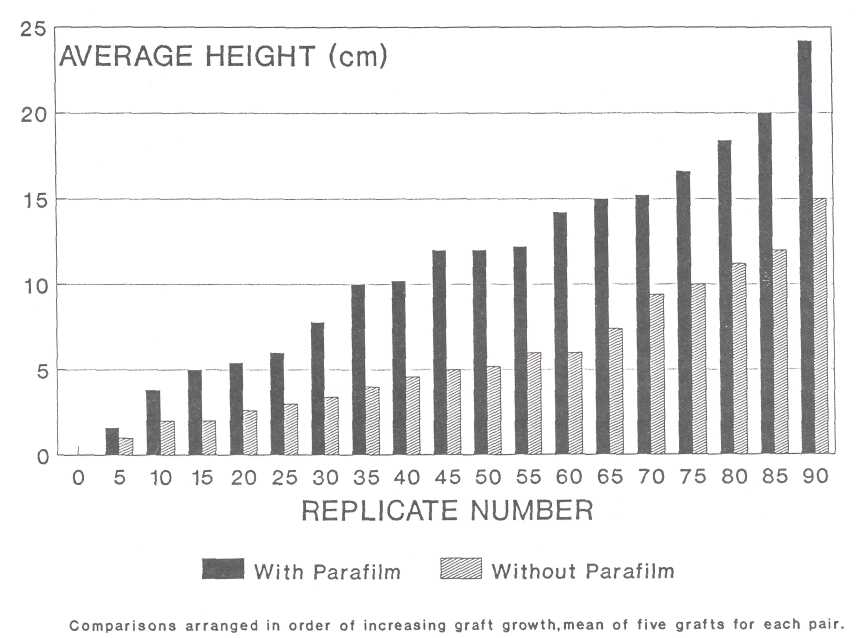

required (Fig. 2). In one large-scale experiment (Fig. 3), by 10 weeks after

grafting, Parafilm treatment had resulted in almost

twice as much graft growth, an average length of 11.6 cm compared with 6.1 cm

for the controls (P < 0.001).

More

experience is needed to utilize the full potential of the Parafilm

product. For example, Mr. Marocco wraps not only the

scion but also the scion/stock cuts, thus making the usual plastic wrapping

unnecessary, and therefore eliminating the need to return at a later date to

cut plastic from the expanding graft. Mr. Marocco's

results have been excellent, but Parafilm is not as

strong as plastic and is not as effective for all grafts. Other nurserymen have

combined the use of Parafilm with budding rubber

bands. Placing the rubber bands over the Parafilm

helps to reinforce the scion/stock union. Like Parafilm,

rubber bands break down with exposure to heat and light. In order to prevent

too quick decomposition, the film must be shielded from direct exposure to

light. Typically, white paper or paper-backed aluminum are

placed over the material. Dilute, light-colored,

water-base paint on the outside of the Parafilm tape

has been used with varying degrees of success. Parafilm

comes in three types: clear transparent, white opaque, and green translucent. We

know very little about the response of white and green Parafilm

at this time.

Wound Compounds

Using

Parafilm on small-diameter scion/stock grafts

eliminates the need for asphalt emulsion as a seal. But, when grafting

larger-diameter stocks, asphalt emulsion is necessary to prevent sapwood drying

and cambium injury. Typically, asphalt is used at a consistency designed by the

manufacturer. It is easy to apply and is an excellent sealant for cut surfaces

and exposed cambium. But, the effectiveness of this sealant can encourage Poria fungal rot to travel through the heart

of the tree causing structural weakness. Therefore, it is advisable to dilute

the asphalt emulsion for general application, using the thicker full-strength

material to fill larger gaps. This treatment has been found to minimize both

desiccation and disease.

Asphalt

emulsion is black and tar-like. If it is exposed to direct sunlight, heat can

transfer to the tender scions and cause severe damage, even if the scions

themselves are not directly exposed. Therefore, cover all asphalt sealant with a white (or light-colored) water-base paint. We are

searching for a light-colored sealant to replace asphalt emulsion, so far

unsuccessfully. It is also advisable to paint the bark of the stock, which is

now exposed to the sun because of tree top removal.

Coverings

In

hot climates, it is best to protect the newly grafted scions with something

like a multiple-layered white paper cone wrapped around the stump, bound with

twine or stapled, and supported with small bamboo stakes or the equivalent. The

stakes keep the paper from sagging from moisture or bird perching. Before

summer heat, cut vents in the side of the cover to prevent heat buildup.

Paper-lined aluminum has been used very successfully as a cover; the reflectivesurface of the aluminum reduces heat buildup. In

a simple test, paper-backed aluminum maintained inside temperatures more than

6.67C cooler than did brown paper wraps, under conditions of sun exposure

averaging 37.78C. The aluminum cover permits successful bark grafting as late

as mid-summer. The aluminum cover may alter the optimum grafting season in our

area (conventionally early March to mid-May) to April-August, when the rootstock

is more actively growing.

Pruning

Frequently,

no training (other than staking) is given to successful grafts. This is a

cultural-care oversight. Neglected topworked trees

appear on the surface to be healthy, but examination reveals competing

structural limbs or weak crotches likely to break under the strain of a crop

load or high winds. After grafting, the newly developing scion commonly has

more than one shoot. At a height of about 15 to 40 cm, it is advisable to pinch

terminal portions of all but the best-placed, dominant shoot to create a strong

central leader. Sometimes repeat pinchings are

desirable to enhance the central leader. In a month or two, the dominant trunk

becomes the established tree and secondary shoots are removed entirely.

After

the above procedure has produced a single strong trunk, upright growing

varieties like ‘Gwen’ can be height controlled by a switch in logic: remove the

tip of the central leader to encourage tree spread. How this response, or other

pruning treatment combinations, will affect tree height and yield is the

purpose of an ongoing study.

LITERATURE CITED

Whitsell, R.H., G.E. Martin, B.O. Bergh,

A.V. Lypps, and W.H. Brokaw. 1989. Propagating Avocados.

|

|

|

Figure 1. Parafilm wrapping stem and buds of avocado scion. |

|

|

|

|

Figure 2. Avocado shoot growth through Parafilm

two months after grafting. |

|

|

|

|

|

Figure 3. Comparative

effect of Parafilm treatment on growth of 'Gwen'

grafts. |

|