Proc. of

Integrated Management of Phytophthora

Root Rot of Avocado in

Daniel Téliz,

Antonio Mora, Constantino Velazquez, Roberto Garcia,

Gustavo Mora, Pilar Rodríguez,

Jorge Etchevers, and Samuel Salazar

Colegio de Posgraduados, 56230 Montecillo, Mexico

P.H. Tsao

Department

of Plant Pathology,

Abstract.

The State of

1. To diminish the population of

the fungus in the soil, without trying to eradicate it.

2. To promote appropriate conditions:

a) to favor the production of roots; b) to favor the development of antagonistic

organisms; c) to establish a natural equilibrium between vegetative growth,

production of fruit and soil microflora.

3. To understand the physical,

chemical and biological action of these strategies in the soil, in the plant

and on the pathogen.

4. To apply or validate the results

in commercial orchards.

5. To integrate the efforts of

different specialists to better focus the work, to better conduct the actions

and interpret the results, and to optimize the financial resources.

Materials and Methods

An integrated pest management experiment

was established in 1982 in a commercial avocado grove in the State of Puebla, Mexico (Téliz and Garcia,

1982). The grove had the following modifications in its general management: 1)

Irrigation from general to individual tree basin flooding. 2) Eight-year-old 'Fuerte' trees, with distinct foliage symptoms and whose root

infection was verified, were severely pruned to reestablish the foliage/root

equilibrium. 3) All trees were chemically fertilized to invigorate them.

Additionally, the following contrasting treatments were applied:

1) Fresh bovine manure (E): (360

kg/tree). (June 82 and 83; Dec 85; April 88)

2) Alfalfa straw (A): (25 kg/tree).

(June 82, January 83, June 83, April 88)

3) Metalaxyl

(M): (2.5 g.a.i./m2). (Five trimonthly

applications from June 82 to June 83; Nov 83; and three biweekly applications

in May and June 88)

4) EA

5) EM

6) AM

7) EAM

8) Control (T) (without addition of

E, A or M; and with the described general modifications in management)

9) Double-control (DT) (without E,

A, or M and without general management modification).

Each treatment was replicated in 7

trees in a completely randomized design. The effect of treatments was evaluated

by the percentage of roots infected by P. cinnamomi,

root weight, canopy appearance and the production of fruit.

Fungus incidence in the rhizosphere was obtained from

a soil mixture of 10 subsamples; fifty roots per tree

were placed in PARPH cultural medium (Jeffers and Martin, 1986). Vigor

parameters were: kg fruit/tree, dry root weight, canopy

appearance assessed with an arbitrary scale from 1 = dead tree to 6 =

excellent growth. Soil microorganisms were isolated in specific media from 10 g

soil/tree dilutions. Vertical (0-20, 20-50, 50-80, and 80-110 cm) and

horizontal (120-160 and 160-200 cm from the trunk) distribution of roots and

associated microorganisms was evaluated. Data was analyzed as a complete random

block and as a split plot design. Means were compared by Tukey, Duncan and orthogonal contrasts. Canopy

appearance was evaluated by Kruscal Wallis

and Fredman non parametric methods. Correlation

between variables was determined by linear and non-linear regressions.

Results and Discussion

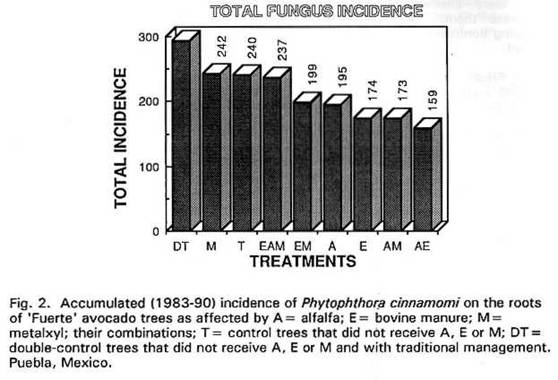

The accumulated effect of the

treatments on fungus incidence (% roots infected by P. cinnamomi

during the eight years is shown in Figs. 2 and 3. Bovine manure (E) or

alfalfa straw (A) alone caused a significant reduction in fungus incidence, but

their separate effect was enhanced when both treatments were combined. Metalaxyl alone did not reduce total incidence of the

fungus as it did when combined with alfalfa or manure. The effect of alfalfa

straw on fungus incidence might be explained by the liberation of saponins (Zentmyer, 1980).

Double-control trees showed the highest incidence of the fungus in their roots.

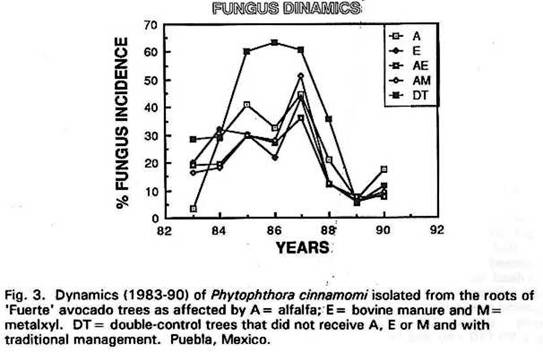

The dynamics of the four most effective treatments from 1983 to 1990 as

compared with double-control trees is shown in Fig. 3. P. cinnamomi was isolated with a significantly higher frequency

from the roots of double-control trees than from the rest of the treatments.

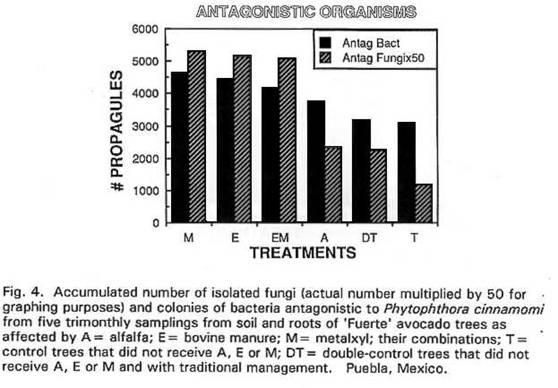

Bovine manure decreased the incidence of P. cinnamomi

perhaps by promoting the growth of antagonistic

fungi and bacteria, as was reported by

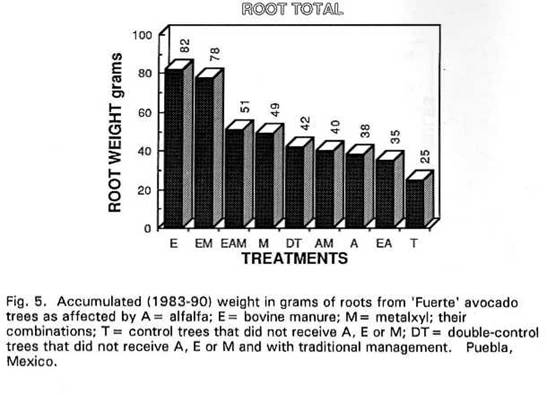

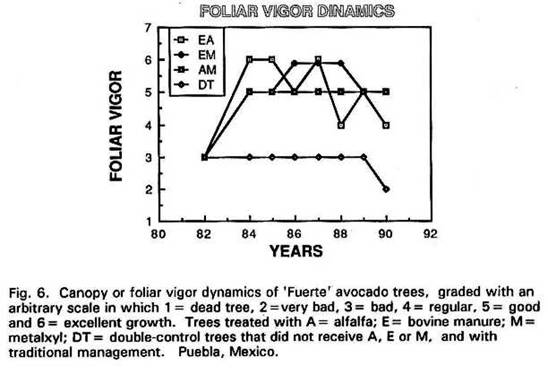

Treatments had a differential

effect on the vegetative growth or canopy appearance of each tree. Dynamics of

this effect from 1982 to 1990 in three of the best treatments as compared with

double-control trees is shown in Fig. 6. The positive effect of

treatments on the appearance of the trees is evident. The

treatments were applied in 1988; it seems that they might be required again in

1991 to improve their appearance to grade 6 (excellent growth).

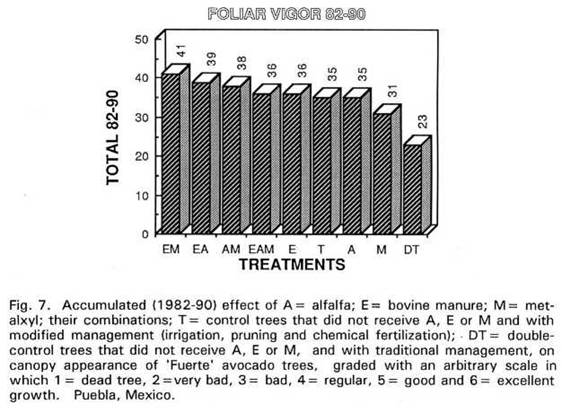

The effect of treatments on canopy

appearance was statistically superior to DT trees, which have remained in a

sustained poor condition. The accumulated effect of all treatments is shown in

Fig. 7.

Soil depth parabolically

reduced the vertical distribution of avocado roots and the number of P. cinnamomi isolations from the roots. The relation between

the amount of root and the proportion of P. cinnamomi

isolations gave an r=0.6194 (P<0.05), a very low value that does

not show a significant relationship between these two

variables. A Spearman coefficient of rs = -0.83, statistically

significant in a test made in 1987, indicated an indirect proportional relation

between the % root infection of P. cinnamomi and

canopy vigor. These type of observations have allowed

the development of methods that do not require root inspection. Zentmyer (1980) proposed a visual scale to evaluate avocado

root rot. The condition of this evaluation is that canopy appearance must be

related only to the presence of P. cinnamomi in

avocado rhizosphere. This condition is difficult to

fulfill under commercial situations, since exclusivity does not usually occur

in nature. Other fungi might be involved in avocado, e.g., tristeza

(Franco, 1983; Kotzé et aI,

1987).

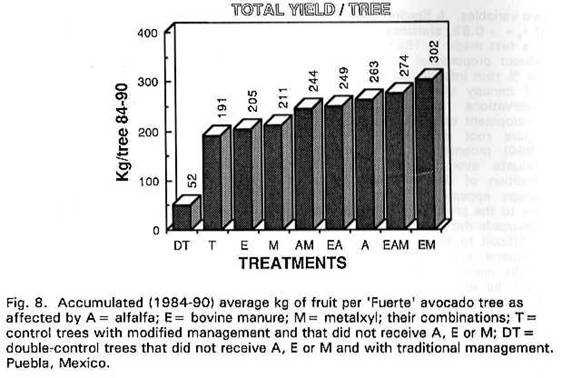

The effect of treatments on fruit

production is shown in Fig. 8. All treatments resulted in a statistically

superior accumulated yield compared with double-control trees (DT). The highest

yield obtained in trees treated with EM represents 580% more fruit than DT

trees. Control trees (T) and trees treated with E resulted in 367 and 394%

respectively more fruit than DT trees, and their marginal return rate indicated

that the treatments were the most profitable.

P. cinnamomi

populations were decreased, but not eradicated by treatments with E, A,

EA, AM or EM. Some treatments favored the production of roots (E and EM) and

the development of antagonistic fungi and bacteria (M, E and EM). Canopy appearance

was superior in all treatments compared with DT trees, apparently

reestablishing a better equilibrium between canopy and root growth,

that resulted in better yields. Control trees (T) and those treated with

E gave the best marginal return rate.

Another experimental plot was

established in 1988 to test the effectiveness of phosphorous acid as a control

measure. Four trunk injections (1.4 g.a.i./injection/tree)

in May and July 1989 and 1990 were applied. P. cinnamomi

populations were decreased and root weight was increased in trees that

received phosphite.

Nutrients dynamics in this project

(Gutiérrez, 1986; Yepez, 1966)

will be published separately. The attempt to understand the results gives us

some insight, but also shows us the kind of data required to make our knowledge

of this disease more precise. The results have been validated on a commercial

basis but not enough to fully understand the disease. Actually we have more

questions than answers.

The authors wish to

acknowledge the financial support of CONACYT and UC MEXUS.

Literature Cited

Broadbent,

P. and K.F. Baker. 1974. Behavior of Phytophthora

cinnamomi in soils suppressive and conductive to

root rot. Austral. J. Agric. Res.

25:121- 137.

Coffey, M.D. 1987. Phytophthora

root rot of avocado. Plant Disease. 71: 1046-1052.

Franco. F, E. 1983. Dinamica de población de Meloydogyne

sp. bajo distintos manejos

Gutiérrez, R. N. 1986. Dinamica

nutricional en arboles de aguacate cv. Fuerte tratados contra Phytophthora

cinnamomi Rands. Tesis. MC. Fruticultura, CP. Montecillo, Méx. 112 pp.

Jacobo-Cuellar, J.L., D. Téliz-Ortiz, R. García-Espinoza, A.

Castillo-Morales y P. Rodríguez-Guzman. 1989. Manejo técnico y aplicación de

estiércol vacuno como alternativa para reducir la incidencia de Phytophthora

cinnamomi en aguacate. XVI Congr. Nac. Soc.

Mex. Fitopatología. Memorias. p.

163.

Jeffers, S.N. and S.B. Martin. 1986. Comparison of two media

selective for Phytophthora and Pythium species. Plant Disease 70: 1038-1043.

Kotzé, J.M., J.N. Moll, and J.M. Darvas. 1987. Root rot control in

Mora, G., D. Téliz, R. García,

and S. Salazar. 1988. Manejo integrado de la tristeza (Phytophthora cinnamoml)

Mora, G., D. Téliz, M. Rosas, and R. Garcia. 1988. Epidemiologia de Phytophthora

cinnamomi en el sistema

radical

Pegg, K.G. and

A.W. Whiley. 1987. Phytophthora

control in

Rodríguez, P. and R.

García. 1985. Manejo

integrado de la pudrición

radical

Rosas, R.M., D. Téliz, R. García,

and S. Salazar. 1986. Influencia

de estiércol, alfalfa y metalaxyl en la dinamica poblacional de Phytophthora

cinnamomi

Soto, M.R. and R. Martínez. 1984. Control químico de la tristeza

Téliz, D. and R.

García. 1982. Manejo integrado de la tristeza del aguacatero. X Congr. Nal. Soc.

Mex. Fitopatología. Culiacan, Sin. Resumen p. 55.

Valenzuela, J.G., D. Téliz, R. García, and S. Salazar. 1985. Manejo

integrado de la tristeza (Phytophthora cinnamomi) del aguacatero en

Atlixco, Puebla. Ann. Rev. Mex. Fitopatología 3: 18-30.

Yepez, T.J.E. 1986. Distribución radical y estado nutricional de la raíz

del aguacatero cv. 'Fuerte' en respuesta a diferentes tratamientos contra Phytophthora cinnamomi Rands.

Tesis MC. Fruticultura, CP. Montecillos, Méx. 85p.

Zentmyer, G.A. 1963. Biological control of Phytophthora

root rot of avocado with alfalfa meal. Phytopathology

53:1383-1387.

Zentmyer, G.A. 1980. Phytophthora

cinnamomi and the diseases it causes. Monograph. 10 A.P.S. 96 pp.