ON AVOCADO FRUIT SIZE II. FRUIT SIZE GRADING

D. N. Zamet

ACCO Experimental Station, Ministry of Agriculture,

SUMMARY

Fruit size grading is an important tool for

evaluating differences between experimental treatments; however, most grading

for this purpose is carried out in commercial packing stations and according to

commercial requirements. Part II of this series of articles on avocado fruit

size shows the difference between commercial grading and what can be called

"accurate grading". It also explains the reason for the use of

accurate grading in this series of articles. The proposition is put forward

that accurate grading, as opposed to commercial grading is a far more important

and sensitive tool for examining experimental results.

INTRODUCTION

Grading by fruit size is one of the most important

parameters for the research worker who wishes to know what effect, if any, a

certain treatment (or treatments) has had on the fruit trees he has been

working with. This grading is usually carried out in commercial packing

stations, or at least according to commercial requirements. In

METHODS

First, a distribution curve for average fruit weight

for commercial grading was drawn. Secondly, 510 fruits of the Ettinger cultivar, the total crop of a few six year old

trees, were picked, marked according to their height above soil level, and each

one weighed on a spring balance to the nearest gram. Maximum height of the

trees was about four meters. Fruit weight distribution curves were drawn

according to two methods. In the first place, the fruit weights were sorted

into groups according to the commercial method and again into 20 gram groups.

In the second place, they were divided into those picked below one meter above

soil level or those picked above one meter. In each of the four cases, the

percentage of fruit in each grouping was calculated.

RESULTS AND

DISCUSSION

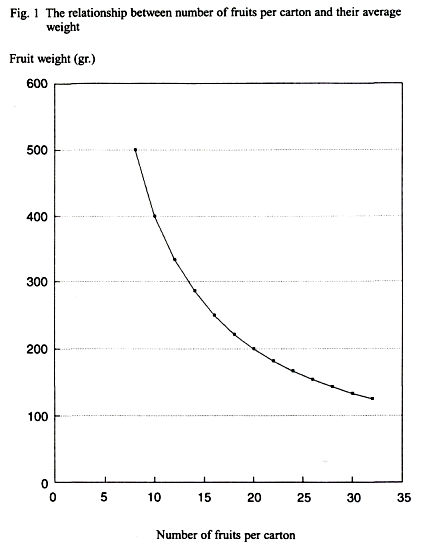

The results of the various gradings

are shown in Figures 1, 2, and 3. In Figure 1 we can see clearly that as the

number of fruit per carton goes down the average weight per fruit increases and

at an increasing rate. Thus, between 32 and 30 fruits per carton there is an

average weight difference of only 8 grams, whereas between 10 and 8 fruits per

carton this has risen to 100 grams! True, even using this method of grading it

is possible to find differences between treatments. However, it is a very

unequal method of grading and cannot show up the fine differences which can be

seen in the accurate method.

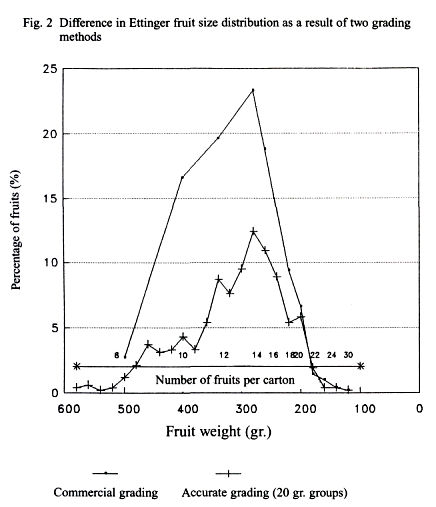

When we examine Figure 2 we can see

the two very different pictures obtained by the grading the same 510 fruits. The commercial method gives a mono-modial distribution curve (which is what we would expect

with regard to the work of Zilka and Klein (5) and

the fact that flowering in the avocado is basically also mono-modial). With the distribution curve of the accurate, or 20

gram, method we have an irregular or multi-modial

curve. Papers which have been published in the last two decades (1, 2, 3, 5) enable us to understand why this multi-modial curve is obtained. It can be understood from these

works that in the 20 gram distribution curve we have a historical record of

climatic conditions and soil conditions prevailing, months prior to picking,

during the flowering period. It must be pointed out again that these two so

different distribution curves are based on the same 510 fruits and on the same weighings. Before we try to learn something from this 20

gram distribution curve, we must bear in mind that Zilka

and Klein (5) have shown that large Hass fruit set before small Hass fruit, and

it seems reasonable to assume that this is true for all cultivars. The first

thing that this distribution curve suggests is that about 2/3 numerically of

the fruit set in the second half of the flowering period. Next, as the peakings are not very sharp, it is suggested that the Ettinger cultivar is not highly sensitive to low minimum

temperature during flowering; it is an accepted fact that Ettinger

is a high yielding cultivar. No big, sudden changes can be seen in the

distribution curve which could be expected if, for example, citrus was acting

as a competitor for the services of the honey bee. Fruit set occurred early in

the flowering period, with some small peaks as the minimum air temperature was

high but still on a very low scale. The fruit set improves very slowly so that

it reaches a maximum only after two—thirds of the flowering period. The fact

that fruit set occurred early in the flowering period, but at a very low rate,

indicates that this was not due to lack of bees or to too low minimum air

temperature but (on the basis of the work of Lahav and Trocioulis

(1)) on the lack of sufficient root activity due to low soil temperature (this

will be dealt with in a further part of this series) or to insufficient roots

left alive after too wet winter conditions (2). Both of these could result in

insufficient moisture and/or nutrient uptake to suffice the needs of the

flowers and very young fruitlets and thus be the

cause of the low initial fruit set. The orchard in question is known to suffer

from drainage problems and the yield in the year the fruit was picked was only

about half the expected level.

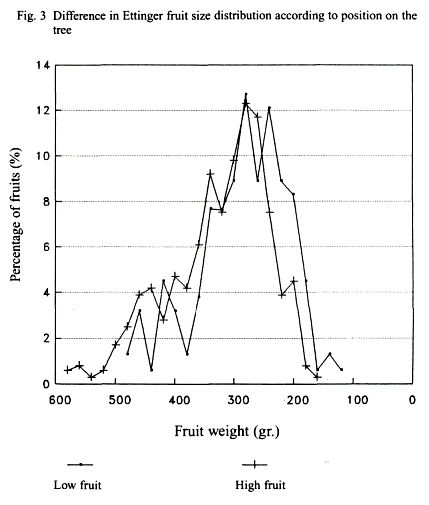

In Figure 3 we again have the same 510 fruits, but

divided into low and high fruit according to their position on the trees. Here

we can see that the high fruit began setting before the lower fruit. Flowering

usually commences a little earlier in the higher parts of the tree. This could

be due to better light conditions, to slightly warmer minimum air temperatures

(unpublished work of Lomas and Zamet),

or to temperature inversion on clear nights. The fact that peaking in the lower

fruit is far stronger than in the upper fruit also indicates that minimum air

temperature in the upper part of the trees was more conducive to fruit set. It

would seem reasonable to accept that any method which will improve soil

conditions prior to and during flowering, and any method which will raise

minimum air temperature, especially during the early part of flowering, will

lead to higher yields and larger fruit.

In conclusion, it is suggested that accurate fruit

size grading, such as the 20 gram method used here (or even the 2 gram method

used for parthenocarpic fruit (4) is an extremely

valuable diagnostic tool which can be used for the understanding of many

problems connected with avocado productivity. It is felt that 200 fruits (or

even as few as 50) can give a reasonable picture, and that therefore the method

is relatively cheap and quick.

LITERATURE

1.

Lahav, E., and T. Trocioulis 1982. The

effect of temperature on growth and dry matter production of avocado plants.

Aust. J. Agric. Res. 33:549-558.

2. Lomas, J., and D.

3. Zamet, D. N. 1990. The effect of minimum temperature on

avocado yields.

4. Zamet, D. N. 1995. On avocado fruit size.

5. Zilka, S., and L. Klein 1987. Growth

kinetics and determination of shape and size of small and large avocado fruits

of the 'Hass' cultivar on the tree. Scientia Hort. 32:195-202.